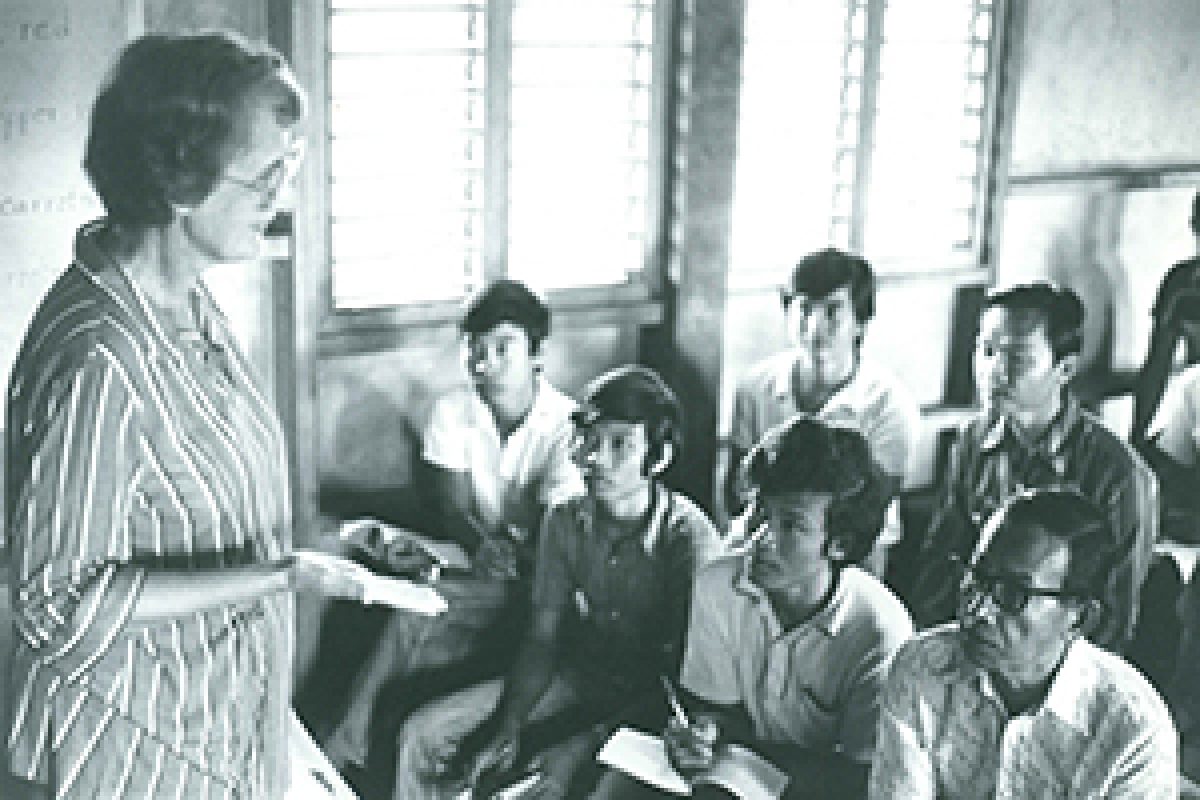

Marylin, ICMC English Teacher in the Philippines, Helped Refugees Start Anew in the 1980s

From 1981 to 1993, Marilyn Fortaleza Omalin worked for ICMC as an English language and Cultural Orientation teacher at the Philippines Refugee Processing Center in Morong, Bataan. In that period, ICMC used to support South-East Asian refugees who had fled conflict in their resettlement process to Canada or the United States. In her position, Marilyn would help refugees prepare for their new life overseas, teaching them not only a foreign language but also the habits and customs of their new country. Marilyn is now living in the United States with her husband Larry, who was also a teacher at the camp.

Where are you from, and what were you doing for a living prior to joining ICMC?

I was born in the City of Iloilo, in the Western Visayan region of the Philippines, where I grew up and completed my education. I graduated with a degree in Education at the University of San Agustin, one of the oldest Augustinian Catholic institutions in the region. I was then offered to teach part-time in the elementary department for almost 5 years.

How did you end up working as a teacher for the refugees being supported by ICMC?

In 1981, I learned from a friend of mine that ICMC Manila was hiring teachers to work in the Bataan refugee camp. We both applied and were hired; we started working at the Bataan Refugee Processing Center in May of the same year. I was assigned to teach English as a secondary language to mixed-level classes of refugees coming from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. Later, I was promoted as Special Teacher, which meant I would not only be teaching English but also conduct Cultural and Work Orientation classes.

I taught mothers and young adults, and got involved into curriculum development, team training, and recruitment. Upon my promotion as Supervisor, I got engaged in curriculum development, supervision of instruction, conflict resolution, and performance evaluation. When ICMC revealed its plans to bring in prisoners of war and launch another program to cater to the needs of this special group, I got further training to deliver such classes. The plan was however halted due to the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in 1991 and the camp was almost shut down because of the damage brought about by the event. I believe that was the greatest challenge ICMC staff had ever encountered.

What type of questions did your “students” frequently ask during their Cultural Orientation classes?

Younger students touched upon American lifestyle, education opportunities, sports, fashion, while older students were more interested in job opportunities, housing, weather, health, finance, or how to deal with the local authorities. Sometimes, they would also ask how to report emergencies or call for help!

What was it like to live and work in a refugee camp?

Life in the camp was very fast-paced and busy. The surroundings were lush and green, so peaceful and quiet. We hosted parties at Christmas time when we would distribute gifts to children and the townsfolk of Morong. We often had graduation ceremonies for students, games, art exhibits, and church services, which made us feel at home away from home.

I met my husband Larry in the camp. We’ve been married for 30 years and we have three children, two of whom were born while in Bataan. We enjoyed living in the camp. I introduced my children to our refugee students and their families and occasionally took them to class. Students would constantly invite us to their homes, where they would tell us stories about Vietnam and Cambodia and how they survived the wars. Even though some stories were chilling and sad, students were eager to share their memories with us.

What did you like most about your job? What was the greatest challenge?

I loved that we received professional training systematically, thanks to the help of local and foreign trainers. Books and research articles were always available to us and up to date. My greatest challenge was to match teaching strategies and classroom activities so that students could truly appreciate their daily learning experience. Students were really motivated and there was never a dull moment in class. If they wanted to be successful in their new life, they knew they would have to learn the new language and culture. It was my dream job. The classroom was my world and will always stay that way.

How did you feel when the camp was closed down?

It was hard to leave the camp. There was so much display of emotions among staff and students. However, thanks to my work experience there, I got hired as a courseware manager at a computer company where I was assigned to oversee curriculum development. My husband stayed longer in Bataan with our second child, while I lived alone in Manila and traveled back and forth to Baguio City where our eldest son studied and lived with my cousins. Larry then left to reunite with us and ended up teaching as an industrial arts instructor. The Refugee Program finally shut down in 1995, when the government decided to convert the camp into a tourist site.

What is the memory you keep most at heart from those years in Bataan?

I served at ICMC for almost 11 years and I am proud of the Refugee Center in Bataan. It was like Ellis Island to me – an epitome of hope, courage, and survival. By meeting countless refugees who had survived so many atrocities, my husband and I were offered a new beginning in pursuit of self-enrichment, rewarding work experience, and educational advancement. Working for ICMC opened my eyes to global politics, educational trends, foreign policies, and many other issues affecting people’s lives around the world.