Catholic Parishes in Egypt Assist Refugees Fleeing Brutal Conflict in Sudan

As the war in Sudan continues with no prospect of peace, Catholic parishes are providing lifesaving assistance and support for those seeking safety in Egypt.

“We’re doctors, we’re educated, we’re qualified, but we’ve lost everything. Now we find ourselves begging for sugar. Why would I smile?”

Father Mina, parish priest of Sakakini parish in Alexandria, Egypt, recalls an exchange with a Sudanese woman he encountered while she was waiting at a parish food distribution center. “She looked sad, so I’d called out to her in a friendly way, to encourage her to smile,” he explains. “After talking with her, I learned she was a pharmacist who had fled to Egypt in 2023 to escape the war in Sudan. Since then, she’d worked as a cleaner but been badly mistreated by her employer, who had eventually accused her of theft. This is how she had come to be in a line waiting for food.”

The Sudanese pharmacist recalled so clearly by Father Mina is one of more than 8.9 million people displaced by a brutal conflict in Sudan that began on 15 April 2023. To date, more than half a million of those forced from their homes have traveled north to seek safety in Egypt.

Fragile peace, brutal conflict: Background to the war in Sudan

Conflict in Sudan erupted on 15 April 2023, when cooperation between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) broke down.

In reality, the roots of the current conflict can be traced back to the early 2000s, when autocratic leader President Omar al-Bashir armed Arab tribes, also known as the Janjaweed, to put down a rebellion of mostly non-Arab militias in the Sudanese state of Darfur.

The war in Darfur resulted in the deaths of approximately 400,000 people from 2003 to 2009. By 2013, al-Bashir had constituted the paramilitaries as the RSF, which in the ensuing years grew to become a formidable rival to the SAF.

In April 2019, following many months of public protests in support of a transition to civilian rule, a military coup led by the SAF deposed and arrested al-Bashir. While international pressure led to the formation of a Transitional Military Council involving both the SAF and the RSF, this move toward transitional government followed the brutal suppression of ongoing protests in support of a transition to democracy.

The integration of the RSF into the Sudanese army became a major point of disagreement in the context of a UN-backed Framework Agreement, launched in December 2022 as a new political process to restore Sudan’s transition to democracy. Escalating tensions in early 2023 finally led to the eruption of conflict on 15 April, when the RSF launched a series of attacks on SAF bases throughout the country. Other factions have since joined the conflict, particularly in Darfur, as have foreign actors, including both paramilitaries and governments of countries neighboring Sudan and those further afield.

A humanitarian catastrophe: The situation in Sudan in 2024

Sudan had been grappling with violence, displacement, and severe humanitarian needs before the current conflict began. By the end of 2022, the country was already home to more than a million refugees, the majority from South Sudan. A further 3.7 million people were internally displaced, the majority of whom were in a protracted situation. The wider security and protection situation in Sudan remained extremely volatile, particularly in Darfur, but also in other areas experiencing resource scarcity, food insecurity, and limited access for humanitarian relief.

Into this already unstable context, the current conflict brought an explosion in violence. Five thousand five hundred fifty events of political violence, 1,400 violent events targeting civilians, and more than 15,500 fatalities have been reported since the war began. Civilians in the small central state of Khartoum have experienced the highest levels of targeted violence, with more than 3,660 recorded incidents and 7,050 fatalities. Civilians in Darfur also continued to suffer disproportionately, with 32% (4,960 persons) of all reported fatalities occurring in this conflict-scarred region.

In a context of significant pre-existing displacement, the current conflict has to date caused 8.9 million people to be displaced. 6.79 million are internally displaced within Sudan, among them 160,000 pregnant women, with an estimated 54,000 births due within the next three months. 1.3 million Sudanese refugees have arrived in neighboring countries, including Chad (579,000), Egypt (500,000), Ethiopia (45,000), and the Central African Republic (24,000). South Sudan has received more than 530,000 South Sudanese refugee returnees, in addition to approximately 144,000 new Sudanese refugees, creating a significant humanitarian crisis. A further 75,000 refugee returnees have left Sudan to travel back to other home countries.

In combination with rising food prices and economic instability, the conflict is also driving a critical hunger crisis. Nearly 5 million people are edging toward famine, while a further 17.7 million face acute food insecurity. Staff shortages, electricity blackouts, and water shortages are critically affecting Sudan’s health sector, with approximately 80% of hospitals in conflict-affected states no longer in function. Since September 2023, a cholera outbreak has affected more than 11,000 people, and more than 7,000 new mothers and 220,000 severely malnourished children are likely to die unless maternal health services and nutritional support are rapidly made available.

While humanitarian needs are critical, access is hampered by insecurity, lengthy and bureaucratic aid clearance procedures, and fuel shortages. Access is also limited by widespread internet and communications shutdowns, which since February 2024 have limited millions of people’s ability to communicate with their families, seek safe zones, and access mobile money transfer services.

Refugees from Sudan in Egypt

Egypt hosts 575,000 registered refugees and asylum-seekers from 61 countries, of which Sudanese refugees are now the largest constituent group. Other major refugee groups are Syrians, South Sudanese, and Eritreans.

The conflict in Sudan has had a stark impact on refugee populations in Egypt. In early 2022, there were 52,446 Sudanese, 20,970 South Sudanese, and 21,105 Eritrean refugees in Egypt. In the intervening two years, the populations of these refugee communities have increased by 472% (Sudanese), 96% (South Sudanese), and 66% (Eritreans).

Newly arrived refugees from Sudan are a demographically vulnerable population. Of those registered with the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), 39% are minors aged 0-17, while 53% are women and girls. At the start of 2024, 22% of refugees in Egypt were living with a disability, and a high proportion of new arrivals from Sudan have chronic health conditions.

Registration with UNHCR is a key challenge for those seeking protection and assistance in Egypt. Newly arrived refugees fleeing Sudan must be registered in order to receive any kind of assistance, requiring travel to Cairo, where UNHCR registration offices are located. This places a significant financial burden on newly arrived individuals and households, and creates protection risks for those who remain undocumented. The surge in arrivals as the conflict progresses has also placed considerable burdens on UNHCR’s registration capacity. At the start of 2024, 168,000 newly arrived people from Sudan had registration appointments but remained unregistered.

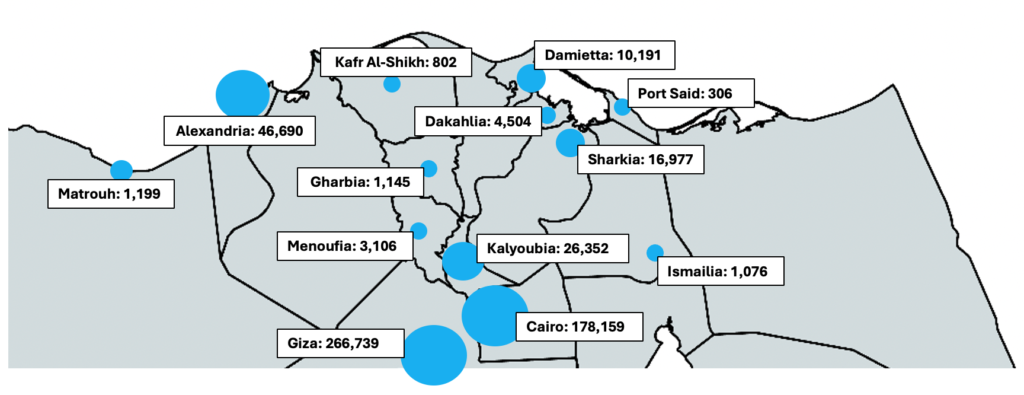

Due to a national ‘no encampment’ policy, the majority of refugees in Egypt live in the urban areas of Cairo and the northern coast.

An overall scarcity of accommodation and high rental costs mean many refugees from Sudan struggle to find housing, with the majority resultantly living in sub-standard and overcrowded conditions.

Although refugees are included in the national primary healthcare system, the high cost of secondary and tertiary healthcare increases the vulnerability of those with chronic conditions. In addition, Egyptian healthcare expertise relevant to Gender-Based Violence (GBV) is concentrated in Cairo, meaning those in border and other urban areas are often unable to access appropriate medical and psychological interventions.

A 2014 Ministerial Decree enabling refugee children to register in Egypt’s public schools was not renewed in September 2023, and both high private school fees and the limited capacity of community schools significantly affected access to education for children and young people. Following a period of intensive advocacy, the Decree was eventually reinstated in November 2023. A new requirement for refugee pupils to provide documentary proof of their registration with UNHCR in order to enroll has, however, placed additional pressure for a rapid expansion of UNHCR registration services.

Assisting refugees from Sudan in Egypt: Situation in the parishes

Since the conflict’s outbreak, Catholic parishes have been providing support and assistance to many of those who have fled to Egypt to seek safety.

Five parishes are specifically dedicated to assisting the large number of Sudanese refugees. Amongst these, Sakakini parish has registered 9,500 new Sudanese refugees for assistance between April 2023 and January 2024, representing a huge increase in the levels of refugee assistance provided by the parish.

“The numbers show no signs of abating, and are in fact increasing,” explains Sakanini parish priest Father Mina. “Of the 9,500 new registrations in Sakanini since the war began, 2,500 were in the first eleven days of January 2024 alone. “Sakanini parish is assisting Sudanese refugees who have settled in the Faysal area, to the west of Cairo. Our challenge is to assess the exact needs, who is most in need, and how we can prioritize our resources in such a dramatic situation,” says Father Mina.

He identifies the most pressing need as the provision of food, which inflationary price rises have made unaffordable for many refugees, and more expensive to provide as aid for many humanitarian agencies. “We currently assist around two hundred people each month with a basic food kit, containing items such as rice, pasta, lentils, flour, tea, and sugar,” explains Father Mina. “The second material need is blankets and clothes, which we provide to those most in need to the best of our ability.”

Father Mina is keen to emphasize that the needs of the Sudanese refugee population are not solely material. “The third major need is psychological support,” he asserts. “We are establishing a workshop project on psychological challenges, to support adults who have suffered in the war. We also organize games and activities for the children, who are in need of distractions from their situation, and have succeeded in enrolling 72 refugee children in mainstream education.”

One Cairo parish is dedicated to supporting Eritrean refugees who have fled Sudan. While their number is lower, settling in Egypt presents a specific set of challenges for this refugee population.

“We have registered 746 Eritrean refugees for assistance from our parish since April 2023,” reports parish priest Father Claude. “A major challenge is that, unlike the Sudanese, the majority of them do not speak Arabic, but rather Tigrinya or another dialect.”

In Father Claude’s experience, the most pressing need among the Eritrean refugee population is access to healthcare. “Many arrive in need of treatment for chronic conditions or diseases,” he explains. “While some hospitals work in partnership with UNHCR to provide refugees with free care, they are often of very poor quality, with absent doctors, and lengthy delays, even for emergency cases.”

Access to food and basic nutrition is also a challenge for Eritrean refugees, in some cases causing malnutrition and vitamin deficiencies in children. “Not being able to buy milk for children, for example, has a severe effect on children’s health and development,” explains Father Claude. “These issues will have health repercussions well into children’s later lives.”

The period in which enrolment in Egyptian public schools was not possible for refugee children also had a severe impact on the Eritrean refugee population in Cairo. “Community schools could not cope with the growing demand, and had to limit the number of pupils they accepted due to a lack of capacity,” he says. “Without education, there’s no stimulation or activities for the children, who end up just staying at home. Where children are enrolled, the high cost of transport means they often miss school.”

While most Eritreans registered with the parish are also registered with UNHCR, and hence legally reside in Egypt, this does not entitle them to any financial support. “Having refugee status does not grant them the right to work, so the only jobs they can do are unofficial and undeclared,” explains Father Claude. “The work they are most in demand for is housework or cooking, meaning it is easier for women and girls to find work, but only with conditions that are very tough and with extremely long hours. In fact, most of those we assist cannot find work, and tend to just stay at home.”

In Father Claude’s view, both pre-existing labor market conditions in Egypt and the wave of refugees that have arrived as a result of the Sudanese conflict have created a population at severe risk of exploitation. “The situation was already difficult before the war in Sudan, but since the war the availability of cheap labor has exploded. Finding a job is an obstacle course, and refugees are more and more exploited, in conditions that are less and less respectful of human rights.”

***

Read the Apostolic Vicariate of Alexandria’s full Report on the Refugee Situation (7 May 2024).

Rachel Westerby

Independent writer and researcher on migration, refugees, and human rights.