ICMC Supports Migrant Workers Devastated by COVID-19 Job Losses in India

A three-month lockdown went into effect nearly overnight in March 2020, leaving people in the urban slums of Delhi stranded or forced to walk for weeks back to their villages, to survive.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been devastating in every country worldwide, but India has been arguably the worst-hit, by far. While the United States has had the highest number of cases of any country to date, the impact of massive lockdowns of businesses and industry for months was softened by a quick leap to employees working from home, distance learning for schools and federal assistance to support people through the pandemic who were losing jobs or lost a loved one – someone who might also have been a breadwinner for the family. Vaccine campaigns were rolled out en force, once vaccines were quickly developed, especially by American pharmaceutical companies. Mortgage payments were largely put in forbearance, and evictions barred.

Now imagine how the pandemic just steamrolled over the lives of millions of vulnerable people in India. Nothing can convey the chaos in a country with few resources to manage a fast-spreading and lethal pandemic. India’s major cities, such as Delhi, Mumbai, and the technology powerhouse Bangalore, are also heavily dependent on the labors of migrant workers from rural villages – some 140 million people according to the most recent census data from 2011 – who keep the cities humming with a steady supply of cheap labour: people laying bricks, hawking fruits and vegetables on the streets or the women who pass their days cleaning or cooking for better-heeled families. Those estimates are conservative, however, based on a Census taken more than a decade ago. Nationwide, that census counted 450 million internal migrants, and it’s known that the trend of massive migration toward the cities for work has constantly continued in earnest, right until the pandemic hit.

In March 2020, suddenly those millions of migrants found themselves in a dire situation, when the government of India implemented its own massive lockdown, in an effort to curb person-to-person transmission of the virus. Millions of migrant workers were out of a job almost overnight, with no savings and no social safety net to soften any of the blow. Transport was also shut down in a matter of days, again to prevent the spread of the virus. Those millions of internal migrants had to walk days, without food and water, but they weren’t fleeing the spread of the COVID-19 virus in urban and peri-urban slums.

“We were overwhelmed just trying to keep people from starving in the early days,” said Rani Punnaserril, a Catholic Sister and program manager for the Conference of Catholic Bishops of India (CCBI)’s Commission for Migrants. For many years, she has been involved with migrant workers in and around Delhi, in response to the excessive and multiple vulnerabilities they face. The Archdiocese of Delhi, its social development arm, Chetanalaya, together with labor rights and domestic workers’ rights associations, were among those that helped many of the poorest people through the worst first three months of strict lockdowns.

“We were overwhelmed just trying to keep people from starving in the early days.”

Sister Rani Punnaserril, Sisters of the Holy Cross-Menzingen (HCM)

“We were also paying some rents so that people and families were not evicted from their homes in the slums,” said Sister Rani. “Not only could people not buy food to feed themselves, but some were being kicked out of their homes in the midst of a brutal heatwave,” she explained. It was so hot at a certain point, that domestic workers’ hours were cut by half, if they were able to return to work at all, once the lockdowns came to an end. After noon, it was simply too hot to cook, she said. But most domestic workers were dismissed and never called back by their former employers. Many never received their legally required severance pay, and some never received their last salaries.

Monica Singh, 36, was one of those women. She had been employed as a domestic worker at a home in Delhi, but suddenly she was fired and not paid money that was due to her. She says she suffered from medical problems and financial stress, and she, her husband and two children had to rely on donated food during the hardest months of the pandemic.

Monica learned about the programs aimed at supporting migrant workers during COVID, supported by ICMC and implemented by CCBI’s Commission for Migrants, relying on funding from the Raskob Foundation, based in the United States. The Archdiocese and CCBI already had a long experience working with domestic workers and grassroots organizations, raising awareness on labor rights so people are empowered to advocate for themselves. Part of the work of the project revolves around ensuring that migrant workers register so that they can access government assistance that was promised to them, which can be a lengthy process.

Many people are also hesitant to register with government agencies, as some people hail from minority communities. Social workers also try to address those fears.

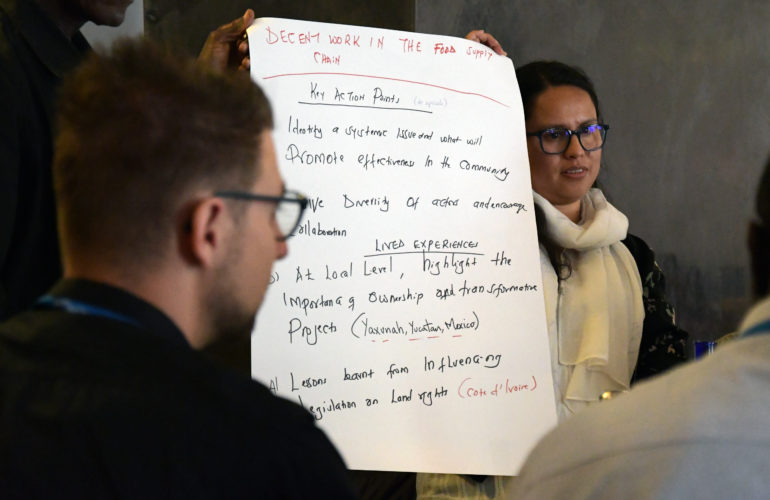

The main benefit available to the many now unemployed migrants in Delhi was a program focusing on making entrepreneurs out of the former employees, so that they could generate their own income independent of an employer, since so many jobs simply disappeared. Monica and more than 500 other people (men and women alike) learned about financial literacy, business planning and management. Then, they would assemble a business proposal and, if approved, each proposal would receive seed funding to get the business launched. In addition to the Indian migrant workers in Delhi, mostly from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and other impoverished areas not far from Delhi, the project supported 20 people who fled from Myanmar, mostly from the marginalized Chin community.

In addition, similar trainings were held in Agra and Meerut dioceses, which were seeing large-scale returns of migrants from cities like Delhi, but where there were no opportunities for work. In those areas, migrants often turned to goat rearing or other agricultural activities to make a new living. Those entrepreneurship trainings were considerably over-subscribed, because people were so interested in signing up. The plan was to train 200 people, but more than 300 people ultimately attended the trainings. Each one received about $200 to start their businesses.

In Monica’s case, she decided to set up a mobile fruit and vegetable cart in Delhi, so she could start earning an income to support her family. Eventually, her husband, Manoj Kumar, also joined the family business, as he had also lost his job during the pandemic. They now can earn almost $10 per day, which allows the couple to provide for themselves and the two children.

The programming also included awareness raising on hygiene so that migrants would know what actions to take to protect their health and the health of their families. Especially in the earliest days of the pandemic, there was considerable uncertainty about the virus, how it spread, and what actions people needed to take, even while having very few resources to do so.