Is the Grass Always Greener on the Other Side? Dispelling Migration Myths in Guinea

For Mohammed, a young Guinean, emigrating to seek better perspectives seemed the obvious thing to do until he actually tried it. Like Mohammed, many young Guineans are pushed to undertake dangerous journeys by dire economic and social conditions. But some grassroots organizations are working to dispel myths surrounding migration.

By Agnès Bertrand (*)

There are about 30 young people gathered in a huge courtyard bordering a busy street of Kindia, the fourth-largest city in Guinea, some 135 km north-east of the nation’s capital Conakry. All sit on plastic chairs as they wait to participate in a discussion on migration.

The session (or “causerie,” in French) has been organized by the Association for Economic and Social Development (ADES), the recipient of a small grant from the Migration and Development (MADE) West Africa program of the International Catholic Migration Commission’s Europe office.

Today, Mohammed, a man in his late twenties, is invited to speak. He returned to Guinea last year after spending 18 months in Morocco, a time that he calls “hell.”

“I walked hundreds and hundreds of kilometers. During my time there, I must have used more than 20 pairs of shoes,” he tells the audience.

“But how did you manage to get 20 pairs of shoes?” someone asks.

Mohammed smiles and answers: “I stole them in the mosques.” And the participants laugh with him.

The anecdote sounds strangely comical… and in sharp contrast with other stories he told a little earlier. Stories about being abandoned along with other migrants by the police near the Algerian border; or being shot at with live bullets while trying to climb the border fence in Ceuta, the small Spanish enclave on the north coast of Africa; or eating food fished out of garbage bins.

Now Mohammed is back in Guinea and works as a fridge repairer. He’s married and doesn’t want to leave home again.

Migration: A Central Issue for Guinea’s Youth

Kindia and its surroundings are the orchard of Guinea. This splendid region is a garden of Eden, but the socioeconomic reality is extremely difficult. Paradoxically, it is one of the regions most affected by food insecurity, which affects 17% of the Guinean population.

Guinea is one of the richest countries in Africa when it comes to natural resources, particularly bauxite, the primary source of aluminum. However, this mineral wealth is exploited by multinational companies who make no effort to redistribute the profits to the local population.

Guinea’s illiteracy rate is around 70%. The employment rate was 66.5% in 2012 and work is predominantly precarious. In 2012, more than half of the population lived on less than USD 1.25 $ per day. In these circumstances, it is not surprising that many young people seek greener pastures abroad and leave the country in hopes of finding work or to study.

The figures speak for themselves. Guinea has a net negative migration rate, meaning that more people emigrate from the country than immigrate to it. In a ranking of African countries as sources of irregular migration, Guinea went from the 8th place in 2004 to the 3rd in 2014.

The phenomenon has reached such proportions that it is a central issue for Guinean society. In this context, ICMC Europe supports the work done by the Kindia-based organization ADES and its partners.

They organize information sessions on irregular migration. The project is supported by the mayor and councilors of Kindia. Some of them are personally involved because they lost a relative on the migration road.

“Irregular migration is a central issue for our society which needs to be addressed with the attention it deserves. Many kids have left and it has created too many dramas. One of the main problems is that despair turns them blind to what to expect on the way to and in Europe, if they reach it one day,” says Ramatoulaye Baldé, coordinator of the project for ADES.

Most of the organizations involved in this work are run by women. One of them, the Association of Women and Girls Leaders of Guinea (AFELGUI), works essentially on women’s rights and emancipation, yet irregular migration is also an important concern for them.

In the words of its president, Salamatou Bourhane Bah: “It is our responsibility as young women and social actors to engage on these issues. Everyone in Guinea knows someone who has left, someone who has come back or sometimes, more tragically, someone who died on the way.”

For her, migration is an issue that touches women as much as men. Sometimes women decide to leave for reasons connected to their gender, such as polygamy, forced marriage or genital mutilation. And for them, the consequences of irregular migration can be dire.

“It is the wives of migrants who have to care for the children on their own, being uncertain about the future. It is the women who, when they leave, are most likely going to be victims of sexual violence on the route. Their body is their passport. When they come back, everyone knows they have most likely been raped and they face social exclusion.”

“Who Will Change Our Society If Everyone Leaves?”

In February, I attended three information sessions run by ADES and its partners (see note at the end for a list of these). Every session is introduced by a facilitator or with the testimony of a migrant who has returned from Libya or of a person who has lost a relative because of migration.

The conversations are lively and usually the young participants split into two camps. On the one hand are those who believe that much remains to be achieved in Guinea. On the other are those who can hardly see any hopeful perspective and want to try their luck elsewhere.

One of the issues underlying these discussions is the idea of success: what does it mean to be successful in Guinea and abroad and what’s the meaning of giving something back to the society to which we belong?

“The perspectives offered to young people are quite limited as we face many challenges in our country,” says Moussa Mara, director of ADES. “The temptation to migrate is understandable, but who will change our society if everyone leaves? It’s up to us, civil society actors, to open up the prospects and help everyone find the resources in themselves to build their own future.”

The project on irregular migration sponsored by ICMC Europe is part of a range of ADES activities such as economic empowerment of women or micro-entrepreneurship, all of which aim to consolidate the social bond, bring hope and create a more just society.

The commitment of ADES staff members to these goals goes beyond their working hours. One of them has set up the first female football team in the region and the director mentors a few wannabe entrepreneurs.

At the time of my visit, a young lady came to his house to work with him on a business plan to set up her dream: a small company to transform fresh fruit into jam or dried fruit. She hopes to get a micro-grant, but knows that these are hard to come by.

Still, they spent the evening working on spreadsheets. And since the neighborhood suffered one of its frequent electricity cuts, they did so with the help of a flashlight (most people cannot afford electricity generators). In the badly-lit room, they discussed cash flows, assets, capital…

I listened to them in silence. This was probably one of the best lessons of resilience I ever received.

(*) Agnès Bertrand is MADE West Africa program manager.

Strengthening Cooperation Between Civil Society and Government

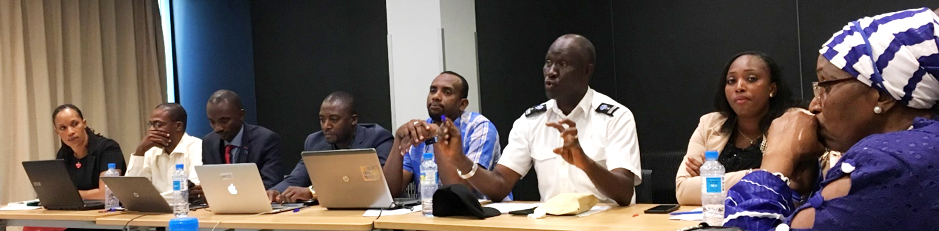

Illegal recruitment practices conducive to migrant-smuggling and human trafficking were the subject of a seminar conducted by the Réseau Afrique Jeunesse de Guinée (Youth African Network of Guinea — RAJ-GUI) in Conakry on 5-6 February 2019. The event was part of ICMC Europe activities to build the capacity of local civil society actors.

Among the participants were government officials (from the ministries of Justice, Social Affairs, Foreign Affairs and Interior) and representatives of civil society organizations, trade unions and migrant returnees.

The talk revolved around how to strengthen cooperation between civil society actors and government institutions to prevent these practices and assist migrant returnees and victims of trafficking. Which is a tough call in the Guinean context, marked by the reluctance of victims and their families to report abuse, inadequate staffing and insufficient means as well as lack of knowledge of the law on the part of those supposed to apply it.

Participants established an advocacy road map to tackle these issues. They expect to use the drafting of the Guinea national migratory strategy as an opportunity to present their recommendations.

Notes:

ADES partners with AFELGUI (Association des filles et femmes leaders de Guinée), CAJEG/K (Coordination des associations de Jeunesses de Guinée, antenne Kindia), CECOJE (Centre d’écoute, de conseil et d’orientation pour jeunes), FEJED (Femmes, enfants, jeunes et développement), GAD (Guinée action développement) and JAJ (Jeune aide jeune).

There are very few statistics available for Guinea. All figures in this article come from the Plan National de Développement Economique et Social 2016-2020 except otherwise noted.